The Tortoise Myth-Busters: Episode 2

- tortoisetrust

- Oct 8, 2023

- 18 min read

Updated: Apr 29, 2024

Sand gets in your eyes... or causes impactions... but does it really?

Testudo graeca graeca in Southern Morocco in a sandy habitat

As usual, we'll start by looking at some advice and opinions from around the web, YouTube and social media. You will find a wide range of such opinions, of course, and in 95%+ of cases that is all they are and all they could ever be. Very, very little (if any) supporting evidence or background material is ever provided to explain why such a conclusion was reached, or any kind of verifiable evidence or proof included that a person could examine or check for themselves. These days, just about anyone can claim to be an 'instant expert' and can spread their opinions far and wide. This has (predictably) resulted in an absolute deluge of misinformation, poorly researched advice, and quite often sensible, rational and well-researched information provided by highly experienced groups and individuals gets completely submerged and lost in this vast ocean of utter nonsense. These short 'Myth-Busters' series are an attempt to set the record straight on a number of specific issues where such misinformation occurs regularly.

In this episode we look at claims that sandy substrates (or those including stones and pebbles) are fundamentally unsafe because they cause either a) Eye irritation or b) Impactions in the digestive tract.

Let's look at a few typical examples of how these claims are presented:

Sand cannot pass through your tortoise’s digestive system therefore if it is accidentally ingested it can cause blockages that can be fatal if not treated.

Most sand used as a substrate has large grains, so it won’t be easy to digest if the tortoise consumes any, especially compared to regular soil.

Sand for substrates is extremely dangerous and will kill your tortoise without a doubt. Tortoises do not ever live on pure sand in the wild.

Obviously sand can’t be digested, and if ingested it can sit in the gut of the tortoise. Repeated compaction of sand in the gut can be fatal, so it is best avoided. Sand is also sometimes mixed with a more moist substrate such as a loam compost to try and provide the balance between being too dry or too moist.....the same risk of sand ingestion/compaction exists, even if it takes longer to be dangerous.

Even if tortoises live in a sandy habitat in the wild, this does not mean it is ideal for them or is safe to copy.

Atroturf is a much better substrate than sand or soil both of which might be eaten resulting in impaction.

I had 4 tortoises on a sand and soil substrate and they all died with impactions within 18 months.

Sand particles can easily enter your tortoise’s eyes as it burrows or plays (?) within its enclosure.

If a tortoise accidentally or deliberately eats sand or gravel then this is very dangerous and it is best to make sure your habitat is cleared of all such material.

Accidental substrate ingestion with food is a danger with ALL loose substrates, but especially with sand because it's heavy and can collect in the intestinal tract.

Some of these sources and pages even label themselves as a 'Tortoise Expert' or 'Tortoise Knowledge' source or numerous similar variations upon that theme. Unfortunately, even a brief read of the content is more than enough to demonstrate just how misleading and untrue that really is. One recommends keeping tortoises in "tanks" and another claims that you have to keep juveniles "permanently" indoors for the first five years of life. This is appalling stuff. Sadly, gullible new keepers might make the mistake of believing them.

Many of these sites and pages appear to be 'cut and pasted' from material copied from other questionable sources (almost never with any acknowledgement) and assembled by people with very little, if any, genuine level of experience or in-depth knowledge. The dietary advice on such sites is typically also incredibly poor and virtually guaranteed to leave anyone who follows it with an irreversibly damaged tortoise. It is no wonder that veterinary surgeons are confronted by a never-ending stream of new keepers with sick and dying tortoises, and that genuinely knowledgeable and long-established tortoise societies and groups have to fight a continuing battle with this unchecked proliferation of potentially lethal misinformation on a vast scale.

So, let us look at the real facts behind the 'sand/grit is dangerous' claim. The first thing to stress is that you cannot just generalise when referring to 'tortoises' as if they were all the same thing from the same habitats. There are many different species, from widely differing habitats, Some species live their entire lives in extremely sandy or stony habitats, some live part of the time in such habitats, and some encounter such substrates rarely. It really is important to differentiate. Species such as Testudo graeca graeca can be found in habitats ranging through very sandy indeed, to moderately sandy, to mainly stony. It varies a lot. Testudo horsfieldii (the Russian or Steppe tortoise, is very similar in this respect). They too are often found in very sandy habitats. Other species such as Testudo hermanni may also be found in a wide range of habitats, some quite sandy, to deciduous and pine forests, to rocky and loamy areas. Again, it is highly variable. Even within a single species and general geographical area you can often find tortoises living on quite different substrates just a few Km apart. Geology, and attitude, as well as the prevailing local vegetation all influence this.

Testudo kleinmanni in Egypt.

Possibly the best way to get an idea of this is to carefully study as many authentic photographs of a particular species in the wild as possible. It is even better to visit such habitats for yourself. In the GALLERY below (click to navigate through it) there are a considerable number of such examples. You may find it useful to study these. Please note that all of these are original images (c) The Tortoise Trust (1984-2023) and have been gathered over several decades of fieldwork with wild tortoises in their natural habitats from all over the world. You may share this page but please give appropriate acknowledgement.

One interesting fact is that among tortoises that do typically live in these very sandy habitats we tend to see certain physiological similarities ('adaptive convergence') where they possess certain physical features that offer better protections or advantages suited to that particular environment. One place where this is often very obvious is in the size and shape of the eyes and also eyelid function. If we compare the eyes of say, a Desert tortoise from the Western United States (Gopherus agassizii) or Testudo kleinmanni (the Egyptian tortoise) to those of say, a Chelonoidis carbonaria (Redfoot tortoise from South America), to a Kinixys erosa (Forest hinge-back tortoise) from Africa, these differences are really profound. They reflect not only differences in the level of physiological protection of the eyes via eyelid development, but also the vast differences in ambient light levels between exposed semi-desert habitats and tropical or temperate forests and meadows. Take a look at the images below - which do you think occur in sandy, arid habitats?

As always, careful study of the anatomical features of a species can be very instructive when it comes to understanding how they live and thrive in particular habitats. This is not to say that you would never find a Redfoot tortoise or a Three-toed box turtle in a habitat where the substrate has some some sand content (they can indeed be found in such localities, though it is not entirely typical of these species as a whole), but you almost certainly would never encounter a population living in habitats as sandy as those that Testudo graeca graeca or Testudo kleinmanni routinely live on in North Africa or that Testudo horsfieldii frequently occupy in Central Asia. So, these are useful 'clues'. Similar adaptions are seen in other desert reptiles, such as snakes and lizards. It would indeed therefore be a bad idea to try to keep a forest species from moist or humid habitats on a highly sandy dry substrate. In very simple terms, they are poorly adapted to it and might very well suffer eye irritation. Equally, if you try to keep a species from very arid, sandy habitats on a very moist substrate do not be surprised if you encounter problems with fungal or bacterial infections of the keratin layer of the shell. Referring to how a species lives in nature is a very good teacher of what is suitable (or not) in captivity.

The evidence from the wild is absolute and incontrovertible. Certain species do indeed live in and on exceptionally sandy substrates and they suffer no harm whatever from it. Either to the eyes or (as we shall see) from impactions either.

This is anecdotal, but we ourselves have worked extensively with wild tortoises within these very sandy or gravel-based habitats for several decades, and we absolutely do not detect evidence that eye-damage from such substrates is any kind of issue at all. If it was, we would see signs of it. We do not. Their eyes cope very well indeed. Refer back to the habitat gallery photographs. We also kept (and successfully bred) many of these species in captive situations (sometimes hundreds at a time) for well over 30 years and again, did not encounter a single case of such damage. It is entirely possible, however, that if other environmental conditions are incorrect, such as grossly excess moisture or humidity, or the use of highly desiccating artificial light or heat sources, then this could be a contributing factor where people do report problems. Certain 'commercial' sand-based substrates sold for 'reptile' use also include other additives that can react in unpredictable ways. We do not recommend the use of these products.

To give an example of just how much pure sand can be blowing around in some of these habitats, this female Testudo graeca graeca in Southern Morocco shows evidence of both 'sand blasting' type wear and the deposition of sand-born mineral deposits ('desert varnish')

One case that we encountered where sand was blamed for repeated eye infections turned out to be due to the fact that the keeper had not changed (or even attempted to clean) the substrate in a rather small indoor habitat for over 2 years. It was absolutely loaded with faecal matter, rotted food, dried urine and assorted pathogens. Hardly a surprise, then, that continual infections occurred. The sand in the substrate got blamed, however, and not the keeper's failure to maintain even rudimentary levels of hygiene.

We just used basic, soft 'play' sand in various combinations with topsoils (which we changed regularly, at least every 6-8 weeks) and that proved safe over many, many years with hundreds of tortoises of various species from semi-arid habitats.

Separating cause and effect is critical, and it is often the case that one thing gets the blame when it is entirely another thing that is truly responsible.

Having established that in terms of any susceptibility of the eyes to potential damage from sand, this is primarily a factor that depends upon matching species to the 'correct' substrates and ensuring that the environment is also suitable and safely maintained, let us now move on to the more challenging question of substrate-linked impactions.

Impactions with sand and gravel can and do occur in tortoises. It is important to recognise this. However, we then need to ask ourselves why this is happening in captivity when it appears not to be a problem in the wild, and when many thousands of experienced keepers have used these exact same substrates without any problems whatever for very many years?

If this really was caused directly by sandy or gravel-rich substrates then there would not be entire populations (even entire species) of tortoises that have not only survived but thrived in those environments for countless millennia. We need to look beyond the obvious and attempt to find the true causes of these issues.

A case of impaction by gravel in a captive tortoise. The animal was severely calcium deficient and was being maintained on a totally unsuitable fruit, vegetable and very low fibre diet.

To give just one example of a genus of tortoise that lives in such habitats, we can take the example of the South African Psammobates. This very genus name literally means 'sand loving'. Logically, if sand and gravelly substrates were truly a threat, then these tortoises would never have evolved and survived for as long as they have.

Psaammobates geometricus in South Africa. This species lives in extremely sandy, arid habitats.

As it is, it is not sand or pebbles now threatening them with extinction, but human activity destroying their fragile habitats and by illegally collecting them. There are other examples too... but the key point is that it is clearly not the substrates themselves causing these issues. Again, please refer to the habitat gallery photos as exactly the same comments apply to Testudo species.

To obtain a reliable answer, we need to ask the right question. The question we need to ask in this case is "why is this not a problem in the wild, and why are only certain keepers reporting sand (or gravel) impactions with their tortoises?"

There are a number of probable co-factors involved. Let us examine these in turn.

Dietary fibre levels.

Experiments in rabbits have shown that high fibre, large particle feeds have a more rapid gut transit time than lower fibre fine particle feeds. Even the exact same feed, with identical chemical make-up, travels through the digestive tract more rapidly as a large particle than as a fine particle (Fraga, 1990 and Gidenne, 1992). Studies by Hatt, Clauss, et. al. (2005) on Galapagos tortoises suggest that if high rates of digestibility in tortoises are to be avoided, the crude fibre content on a DM basis needs to be in the order of 30 to 40%.

Our own studies on Testudo graeca graeca in Morocco and Spain suggest that a similar level of fibre content is typical of natural intake. By contrast, virtually all captive diets are catastrophically deficient in overall fibre content, and especially so in long fibres. The typical “supermarket salad” diet is also seriously inadequate in several other parameters for reasons well-established elsewhere (Highfield, 2000). Such diets tend to be not only very low in fibre content, but are far too high in readily digestible starches and sugars which encourages hyper-fermentation within the digestive tract. They are also extremely high in fluid content. This may appear to be a good thing at first glance, but it in no way approximates the fluid content of a wild diet. Observations over three decades in the wild in Spain, Morocco, Tunisia, Italy, Greece, Turkey and southern France instead support the view that Mediterranean tortoises consume a diet with very low to moderate water content, and instead take advantage of fresh drinking water on an irregular opportunistic basis, from ponds, streams or during seasonal episodes of precipitation. Some highly specialised species, such as Testudo klienmanni, have also been observed to drink dew early in the morning deposited as a result of sea mists entering the periphery of the desert (Highfield, pers. obs).

It should be noted that there is a very significant difference in the ability to suspend and transport particles between a 'mushy, wet' dietary intake and one that contains high levels of coarse, dry and undigestible long fibres. This is the case even if, on the latter diet, the tortoise then drinks fresh water. In this case, the fibres will swell, but they in no way lose their ability to suspend particulate matter and transport it through the system.

It is far safer, and more 'natural' to provide a very high fibre diet with a mixed fresh vegetation and dry content and to provide fresh drinking water separately than it is to provide a diet that is too high in fluid content and too low in fibre content.

A combination of a diet that is extremely low in fibre content (most captive diets are in the 12-18% range compared to the 30-40% range typical of a wild diet) combined with a consistently high fluid content has the effect of making the gut contents far more motile and less well able to transport ingested material through the GI tract. If the tortoise is on a diet that includes fruit and vegetables the effects are particularly severe as these contain almost no long fibres and are far too highly digestible. Their 'residues' are minimal and typically very wet indeed when compared to the residues of a more natural diet (such diets are also dangerously high in phosphorus content and promote excessive fermentation - but that is outside the scope of this particular article). Heavier incidental items that might be incidentally consumed, such as gravel, therefore, will often accumulate (via gravity) rather than be continually moved along and subsequently expelled supported by coarse fibres along the entirety of their journey through the digestive tract. This is very obvious when we carefully examine faecal pellets from wild tortoises. Yes, there is grit, gravel, small stones and sand present - but it is encapsulated, supported and surrounded by the semi or undigested fibres of the plant material consumed. It is very instructive to compare the faecal pellet outputs of wild tortoises on a natural diet to those of typical captive tortoises. The differences are dramatic. Here's something you can do right now. Check your own tortoise's output. How does it compare to these from wild examples?

A faecal pellet from a wild Testudo graeca graeca in Almeria, Spain. Take note of the substantial amount of encapsulated and suspended sand and gravel. Also note the very high fibre content.

There are two main factors here: fibre AMOUNT and TYPE, and also FLUID CONTENT. If we have a diet that is close to the natural makeup of an arid habitat or grassland tortoise diet it typically has a very high percentage of long and medium-length indigestible fibres and a relatively low fluid (water) content. A typical captive diet is the exact opposite. Very low in medium and long fibres and with a very high fluid content. For more on this see our other article (old website) on just how critical dietary fibre is for these species. That also includes many more examples of wild faecal pellets.

The exceptionally high long fibre content of a wild Testudo diet is very obvious here, comprising coarse stalks and similar undigested or only partly digested matter. Even when fresh green vegetation is available, tortoises will sometimes choose dried matter out of preference.

The net effect of this is that the wild diet is very good indeed at transporting ingested materials safely through the digestive tract, while the captive diet is nowhere near as effective (in the worst cases almost completely ineffective) and this can lead to heavier ingested particles becoming 'trapped' and building up internally. This is when impaction occurs.

The real issue here is not the substrate as such, but failure to provide a suitable diet. Even if tortoises on such diets are removed from the 'danger' of any kind of substrate ingestion, there will still be long-term negative effects resulting from the inadequate diet.

The solution is not to avoid natural and normal substrates, but to correct primary dietary deficiencies and other causal factors. Impaction is a secondary condition that is directly caused by deficiencies in diet, temperature regimes, or other inadequate conditions in captivity.

Dietary mineral levels.

Another dietary-related aspect of this that has been observed in a number of reptile species is that where mineral levels (especially calcium) are very low in the provided diet, animals may attempt to correct this by actively eating small stones and other substrate material. This, in turn, will result in a proportionately high intake of such items. This behaviour is known as 'geophagy'. It is quite common especially in the case of herbivorous reptiles (Sokol, 1971). It has also been documented in more than 100 primate species (Pebsworth, et. al, 2019). Again, this is a complex area and not all aspects of it are fully understood, but fundamentally it appears to reflect a need for additional minerals or bioactive substances that the diet provided is deficient in.

Analysis of typical sandy substrates that tortoises live on in the wild reveal a makeup that includes silica, fine clays, calcium sulfate dihydrate (gypsum), iron oxides, silt (rock and mineral particles larger than clay, but smaller than sand), plus assorted grit, pebbles and rocks. Dead, weathered white snail shell particles, which are almost pure calcium carbonate, are also extremely common both on the surface and mixed in with the substrate. Red sands, typical of certain areas in North Africa where Testudo graeca and Testudo kleinmanni occur, contain very high levels of iron oxides, for example. The precise makeup varies from one location to another, but these are the main 'ingredients' in substrates found in the natural habitats of many semi-arid and grassland species. They are not, of course, fully 'digestible' as such, but certainly some useful trace minerals could be obtained from them as they pass through the digestive tract. The bulk of this substrate material simply passes through in an unaltered form. The main thing to be aware of is that if consumed for any reason, whether deliberately or incidentally, it is essential that the 'transport mechanism' (dietary fibre and suitable temperatures) are present at sufficient levels to ensure a safe passage rather than allowing such items to become static and to accumulate internally. In the wild that is not a problem, but in captivity, on fibre deficient and otherwise incorrect diets or housed in unsuitable enclosures it certainly can be.

A female Testudo graeca found near Taroudant in Southern Morocco, on a very sandy substrate rich in iron oxides, causing that very obvious red colouration. This substrate was also very high in calcium carbonate content.

Many captive diets are entirely inadequate in calcium content, and are far too high in phosphorus content. That combination is almost designed to send a tortoise on a 'mission' to find a corrective or compensatory source. A sufficient source of magnesium is also required as this constitutes up to 0.75% of bone ash mass (Robbins, 1993). It is often stated that an 'ideal' ca:P (Calcium to Phosphorus) ratio of a herbivore diet should be 2:1, though many natural habitats include highly calciferous soils, and plants grown in such environments can have very much higher ratios, up to 17:1 in the case of certain plant species that occur in such environments (Gebremariam, et.al, 1996). Even higher ratios have been reported elsewhere. It would therefore seem a good strategy to assume 2:1 to be a practical minimum and to ensure that higher levels are available on a regular basis either through careful food plant selection or via supplementation in captive situations via a phosphorus-free calcium product. Obviously, sufficient levels of both UV-B and radiant heat are also essential components of this process.

Temperature

Chelonia (tortoises and turtles) are reptiles, poikilotherms who regulate their temperatures and metabolisms by relying upon behavioural means and environmental sources of heat. For them to function correctly, they must be provided with a range of temperatures appropriate to their species and must be given adequate facilities within their habitat to make such adjustments to their body temperatures as required. In practice that means access to direct radiant heat, to open spaces and shade, and to suitable substrate temperatures and air temperatures, etc. They use some very complex behaviours to moderate their metabolisms according to need. That is why it can be very difficult to design truly suitable habitats in captivity. In fact, the entire topic of reptilian thermoregulation and thermodynamics is a fascinating separate study area all of its own.

Insofar as impactions are concerned, however, there are a number of very clear pointers.

If the temperatures provided are incorrect this has a direct and profound effect upon the entire digestive process. If the animal is incorrectly 'warmed through' then although the upper part of the body may appear warm enough, the core body temperature (CBT) may be seriously inadequate, Similarly, artificial base-heating using heat pads or mats can disproportionally warm up the lower body (plastron) and a situation can occur where the digestive tract is in 'fermentation overdrive' (especially if there are other serious dietary failures as outlined above) while the rest of the metabolism is slowed down by cold... we are being somewhat simplistic here (this is a very complex topic) but that is the general effect. Incorrect temperatures can slow down or accelerate gut motility, fermentation processes, and in turn the transit of material through the digestive tract.

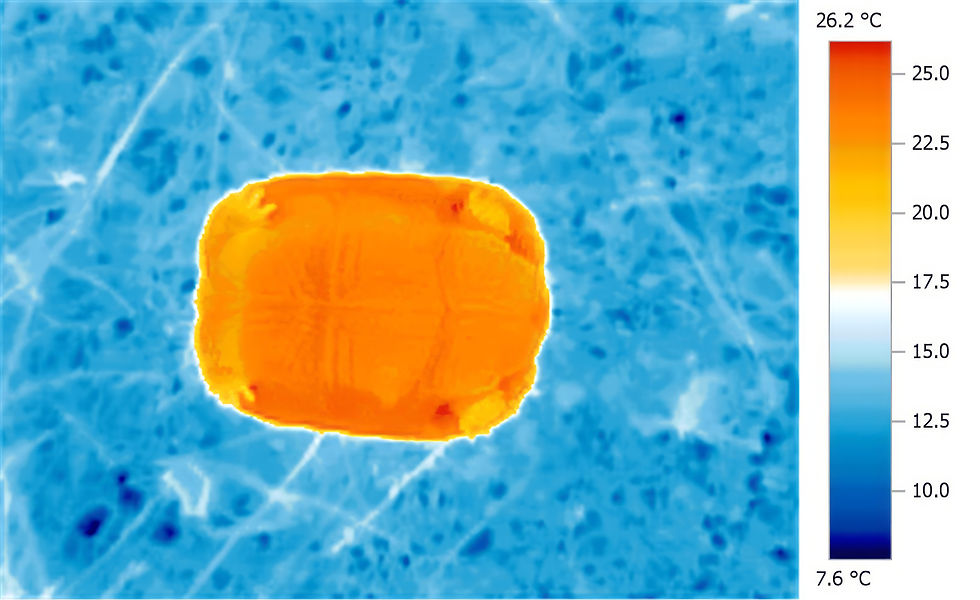

The all-round, all-through and exceptionally even heating pattern resulting from basking under natural solar WiR-A (Infra-red filtered by the atmosphere). This has utterly different properties to the IR wavelengths produced by typical artificial heat sources. There are no extreme and unbalanced 'hot' and 'cold' spots on the body as usually occur under artificial basking heat. This has important implications for the metabolism and for digestion.

The solution is to understand what your tortoise really needs in terms of temperatures and gradients (this varies by species), ensure that the environment at least meets their minimum needs, and to monitor things closely. It should go without saying that it is impossible to provide a truly suitable habitat and range of temperatures in small, enclosed units.

The same tortoise measured a few moments later demonstrating the 'all-though' warming effect of natural solar radiation, reaching right through to the plastron region.

Tortoises require significant space for exercise (another area where many captive environments fail badly) and also a suitable and adequate range of temperature options within their environment. Given sufficient options, they are very good indeed at making the right choices. See our specific advice on this targeted for various different species.

To conclude. Sandy, gritty and pebble-strewn substrates are extremely common in the habitats of many species, from Mediterranean tortoises, to Desert tortoises in the US, to many species in Southern Africa, Asia and elsewhere. Tortoises are well-adapted to live on these perfectly safely. Quite frequently this IS ingested, usually incidentally but in some cases quite possibly deliberately. There is zero evidence that this is problematic in any way. If problems do occur in certain captive situations, we need to look very closely at those particular cases to determine why a substrate which is normally perfectly safe is now associated with a problem. Invariably we find other serious failures of husbandry present, usually serious dietary deficiencies or excesses, a failure to provide an adequate thermal environment, or both.

Bradshaw, S.D, 1986. Ecophysiology of Desert Reptiles. Academic Press.

Fraga, M. 1990. Effect of type of fibre on the rate of passage and on the contribution of soft feces to nutrient intake of finishing rabbits. Journal of Animal Science 69:1566-74.

Hatt, J. M., Clauss, M. and Gisler, R. (2005): Fibre digestibility in juvenile Galapagos tortoises, (Geochelone nigra) and implications for the development of captive animals. Zoo Biol (24): 185-191

Highfield, A.C. 2000, The Tortoise and Turtle Feeding Manual, Carapace Press.

Gebremariam, T. Solomon Melaku, Alemu Yami (1996), Effect of different levels of cactus (Opuntia ficus-indica) inclusion on feed intake, digestibility and body weight gain in tef (Eragrostis tef) straw-based feeding of sheep, Animal Feed Science and Technology,Volume 131, Issues 1–2.

Gidenne, T. 1992. Effect of fibre level, particle size and adaptation period on digestibility and rate of passage as measured at the ileum and in the faeces in the adult rabbit. British Journal of Nutrition. 67:133-146.

Pebsworth, Paula A.; Huffman, Michael A.; Lambert, Joanna E.; Young, Sera L. (January 2019). "Geophagy among nonhuman primates: A systematic review of current knowledge and suggestions for future directions". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 168 (S67): 164–194

Robbins, C. T. 1993. Wildlife Feeding and Nutrition, 2nd ed. Academic Press, San Diego, 352 pp.

Sokol, Otto M. “Lithophagy and Geophagy in Reptiles.” Journal of Herpetology, vol. 5, no. 1/2, 1971, pp. 69–71.

Kommentare